Solar Orbiter and the Sun's poles: a new era in solar physics

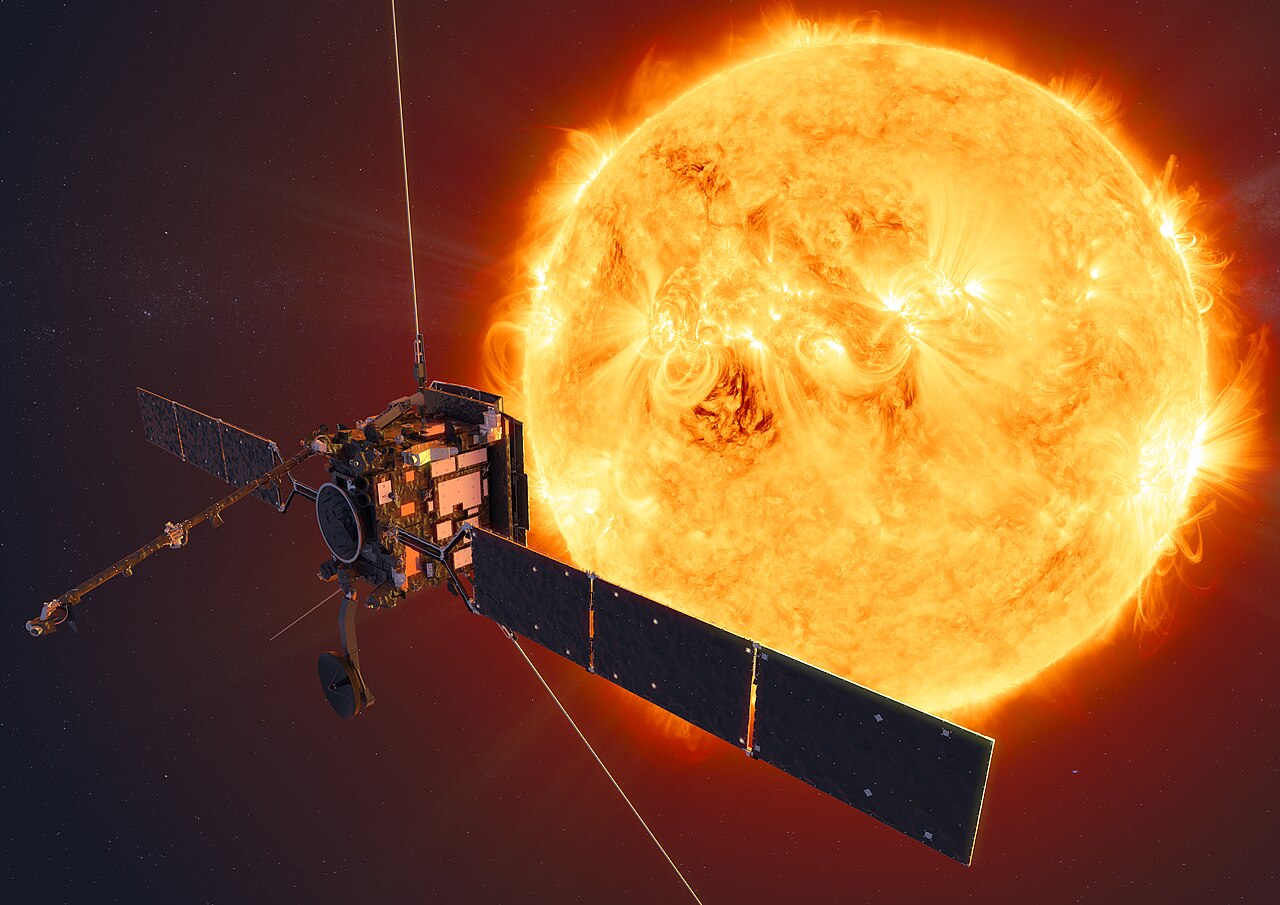

Of the countless space missions exploring the solar system, one has risen above all others, in the literal sense. Solar Orbiter, launched in 2020, has gone where no other spacecraft has ever ventured. Through daring manoeuvres, it broke free from the ecliptic plane to turn its sensors toward uncharted territories: the poles of the sun. In March 2025, this long-elusive last frontier of our star finally came into view. This exciting solar mission is a joint effort in which Belgium plays a prominent role.

By Kathelijne Bonne. This article appeared first in the Belgian science magazine EOS Wetenschap.

To understand what Solar Orbiter will reveal about the sun's polar regions, EOS Wetenschap spoke with two leading solar physicists, both from Belgium: Anik De Groof is ESA's Solar Orbiter mission manager, and David Berghmans of the Royal Observatory of Belgium is chief scientist of the Solar Orbiter's EUI instrument (Extreme Ultraviolet Imager) that explores the sun's corona.

Unresolved questions about the Sun

Processes at the Sun's poles could help answer some of the most fundamental – and still unresolved – questions about what is happening in and around the Sun. For example, We don't yet really know how the magnetic field is being generated through the solar cycle, why the solar wind accelerates, and why the corona – the sun's thin outer atmosphere and only visible during a total eclipse – is so much hotter than the sun itself.

Solar Orbiter, led by the European Space Agency (ESA) with strong participation from NASA, is primarily a scientific mission: it aims to lift the veil on these mysteries. On board, the spacecraft carries ten instruments designed to support this effort. Besides from fundamental science, the new stream of information will also help improve predictions of space weather and its effects on Earth.

Solar Orbiter: first view of the poles on 22 March 2025

Anik De Groof, David Berghmans and their co-workers were among the first earthlings to see the poles of our star, even before the images flooded the media. The south pole of the sun became visible for the first time on 22 March 2025, five years after launch of Solar Orbiter and just a few days after a very risky slingshot maneuver (see further on). Things will get ever more exciting, because more than ten flybys of the poles are still to come.

In previous years, Solar Orbiter has already delivered astounding images of the full sun at a higher resolution than ever before. "You can just keep zooming in and lose yourself in the solar surface" or "I can't stop staring at the images", were the words of Anik and David, respectively.

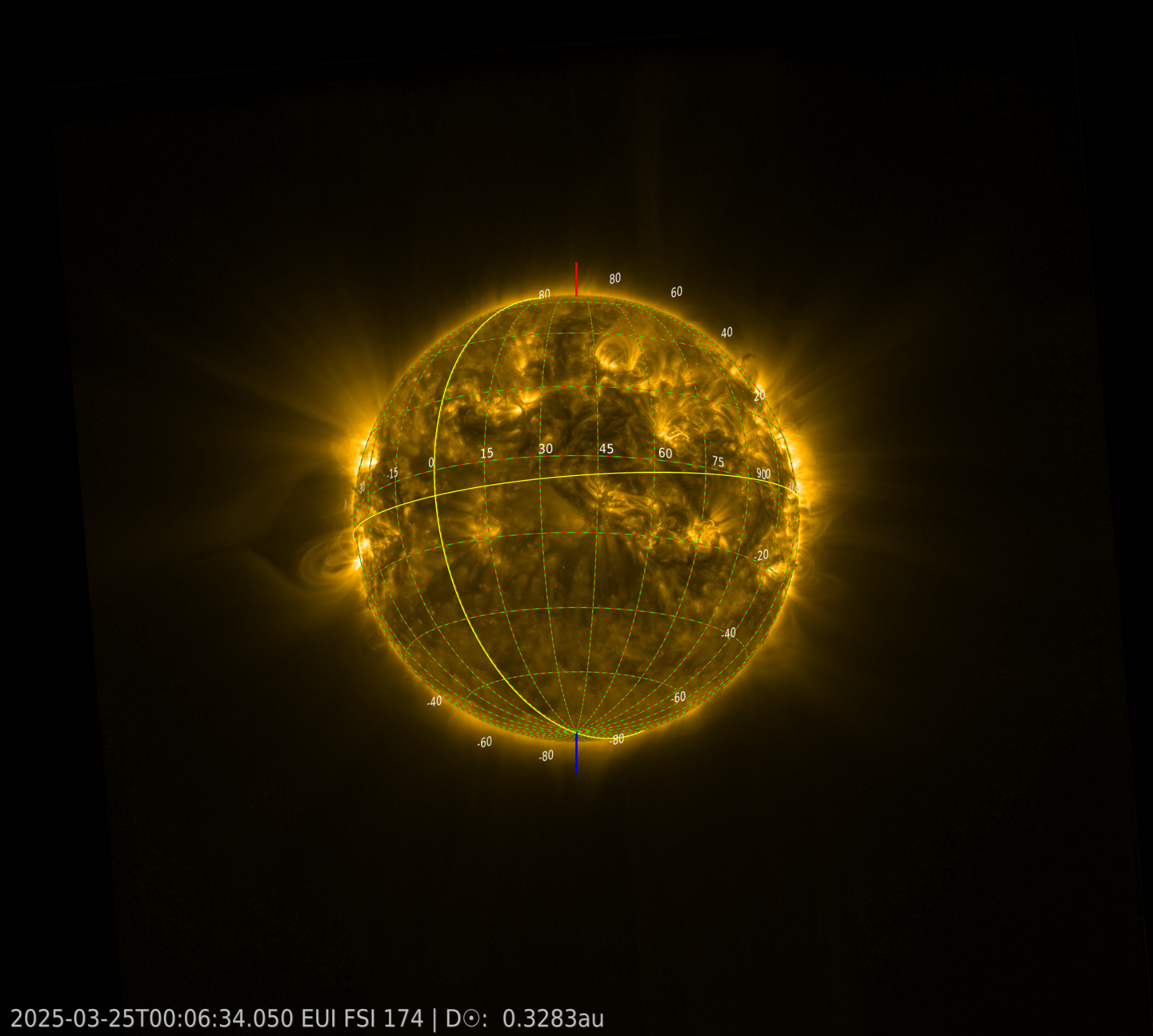

But what really happens at the poles was still uncharted territory at that point. Until March 2025 when Solar Orbiter made a daring plunge below the ecliptic plane – the plane in which the planets and the Sun lie – and looked at the Sun from an angle of 17 degrees. What did the spacecraft make visible?

Strange first glimpses of the south pole of the sun

"At first glance, I didn't see anything unusual", says Anik about her very first impressions of the south pole. "I saw those first images on my phone when I was hiking in nature. It was a low-resolution image of the full sun taken by the Full Sun Imager of the EUI (Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager) instrument."

David thought the sun looked strange in the very first images of the south pole – "especially because until now we had only looked at the sun from within the ecliptic plane. We've only seen the sun with the equator in the middle. Now we're seeing a slightly tilted sun. I was even a tiny bit disappointed because we didn't see any cool structures such as hexagons or vortices like those at the poles of Saturn or Jupiter, nor did we see any eruptions or solar flares like the ones closer to the equator." And after those first views, the satellite moved away from Earth, causing a delay in data transfer. "All we could do was sit and wait for new images and more detail."

Chaotic mess of poles

A few weeks later, higher-resolution material started to trickle in. Images were also processed to make them easier to interpret. "The PHI instrument (Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager) observes the magnetic field. We saw several small magnetic poles. Both positive and negative", Anik reports. "The high-resolution images from the EUI also showed much more structure and detail than the first overall images. Videos already showed some swirling. And although we are careful not to over-interpret what we're seeing at this point, we can already confirm that during the current solar maximum, there is not one single large magnetic pole. At the moment, we are seeing more of a chaotic mix of poles, structures reminiscent of other places on the Sun."

'Quiet' corona during the solar maximum

"What the EUI's extreme ultraviolet images show at the south pole," David continues, "is actually a normal quiet corona, a calm corona without much activity or structure. On closer inspection, this calm state at the pole is to be expected at solar maximum. Right now, we are in an active phase of the current solar cycle. In the EUI images, the activity is mainly visible in two bands at about 30° above and below the sun's equator. The magnetic polarity of the Sun is in the process of reversing. The new polarity has not yet settled. This is probably why we only see the 'background corona' at the poles. This is actually good news: we are going to witness how the new phase of the solar cycle unfolds. During the upcoming flights over the poles, we will see how the solar landscape gradually changes!"

"We therefore expect more exciting developments in the coming months and years, as Solar Orbiter will whizz past each solar pole at least 14 times. Our view of the poles is becoming ever clearer as Solar Orbiter slowly adjusts its orbit to a steeper angle with respect to the ecliptic."

Gravity assist with Venus

Launching a space probe above the ecliptic is no easy feat. After all, there is a reason why most celestial bodies and space missions are located in a flat plane – the ecliptic: it is energetically the best place to be. There is no energy on board to independently break free from the comfortable inertia of the ecliptic plane. "Solar Orbiter uses the gravity of other planets, including Venus and Earth, to bend and tilt its orbit. To do this, it performs gravity assists using planets as slingshots. The images that appeared in the media from March onwards are the result of already the fourth gravity assist with Venus," says Anik.

"This fourth and crucial slingshot manoeuvre – a high precision flyby past Venus – was very risky. After skimming past Earth again in 2021, Solar Orbiter shot very close to Venus on 18 February 2025, at a nerve-wracking 379 kilometres from the Venusian surface. That is closer to Venus than the International Space Station is to Earth. The closer you get, the more speed you can pick up. But it also becomes riskier due to dangerous interactions with Venus and its atmosphere."

Fortunately, the spacecraft navigated throught this momentuous gravitational maneuvre safely and emerged below the ecliptic with the south pole of the Sun in sight. The Solar Orbiter will "refuel" at Venus a few more times to increase the angle of its trajectory with each orbit – to an angle of 33 degrees. The orbit is also designed so that the satellite is closer to the Sun than Mercury at its perihelion and never further from the Sun than Earth. This enables Solar Orbiter to see the sun up close as well as to study space weather in the heliosphere around Earth.

When asked whether the Solar Orbiter is the first 'out-of-the-ecliptic' mission, Anik's answer is no. "In the 1990s, the orbit of the Ulysses mission was brought to an immense angle of 80 degrees. The catapult effect of massive Jupiter was used to execute this daring cosmic maneuver."

"However, what is groundbreaking about Solar Orbiter is that it comes much closer to the sun and also literally sees and images it. Ulysses did take measurements – including of the solar wind – but did not 'see' the Sun." Solar Orbiter has several eyes that gaze directly into the face of the sun, through tiny pinholes in its heat shield. And in addition to 'seeing', a form of remote sensing, some instruments also take in-situ measurements of particles, waves and radiation.

Coronal holes: will we see how they form?

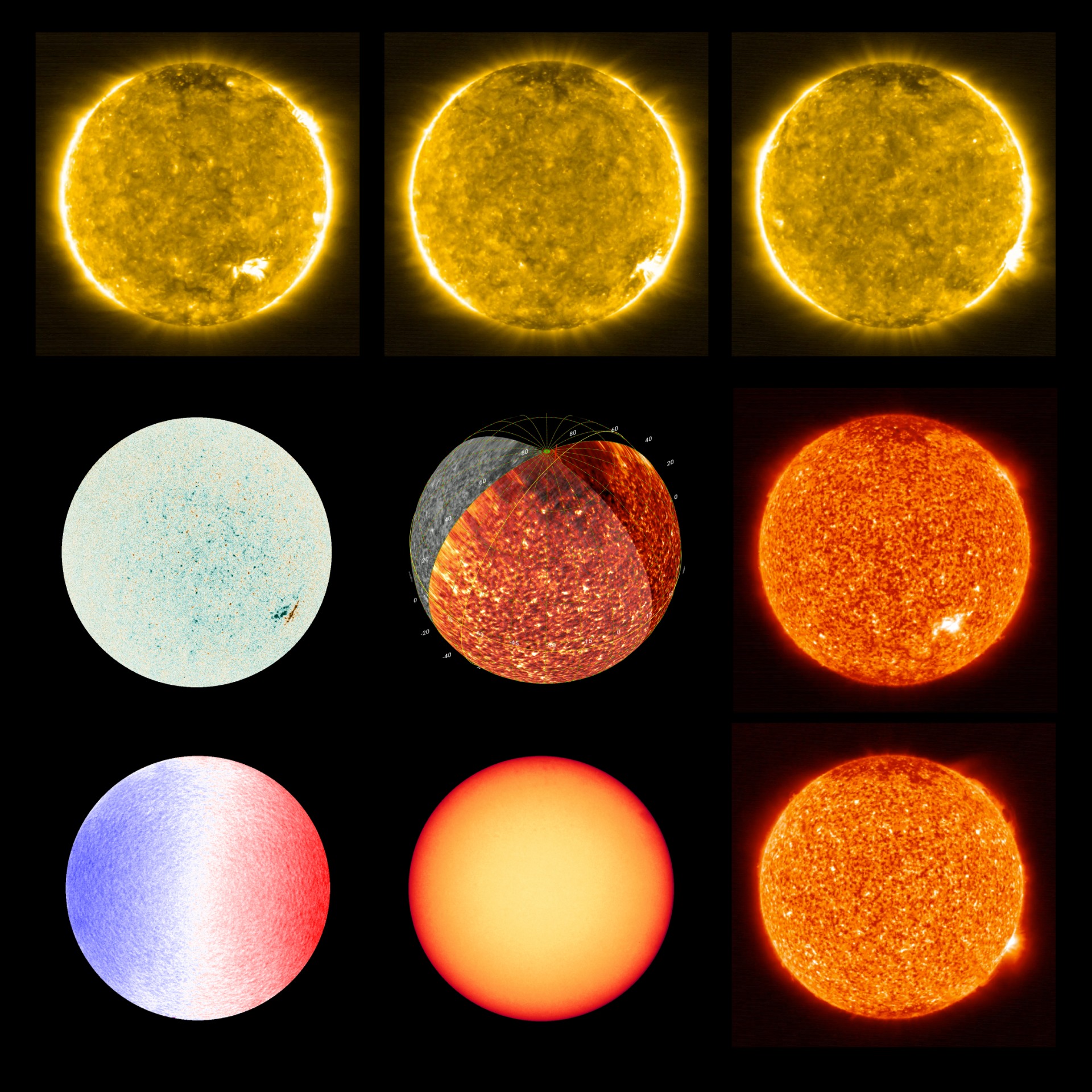

The light emitted by the sun radiates a continuous spectrum of radio waves, infrared, visible, ultraviolet and X-rays. By looking at specific parts of this spectrum, distinct aspects of the sun can be studied. However, the total radiation is relatively constant over geological time scales, and this is why we have a more or less stable climate that has allowed complex life on Earth for hundreds of millions of years.

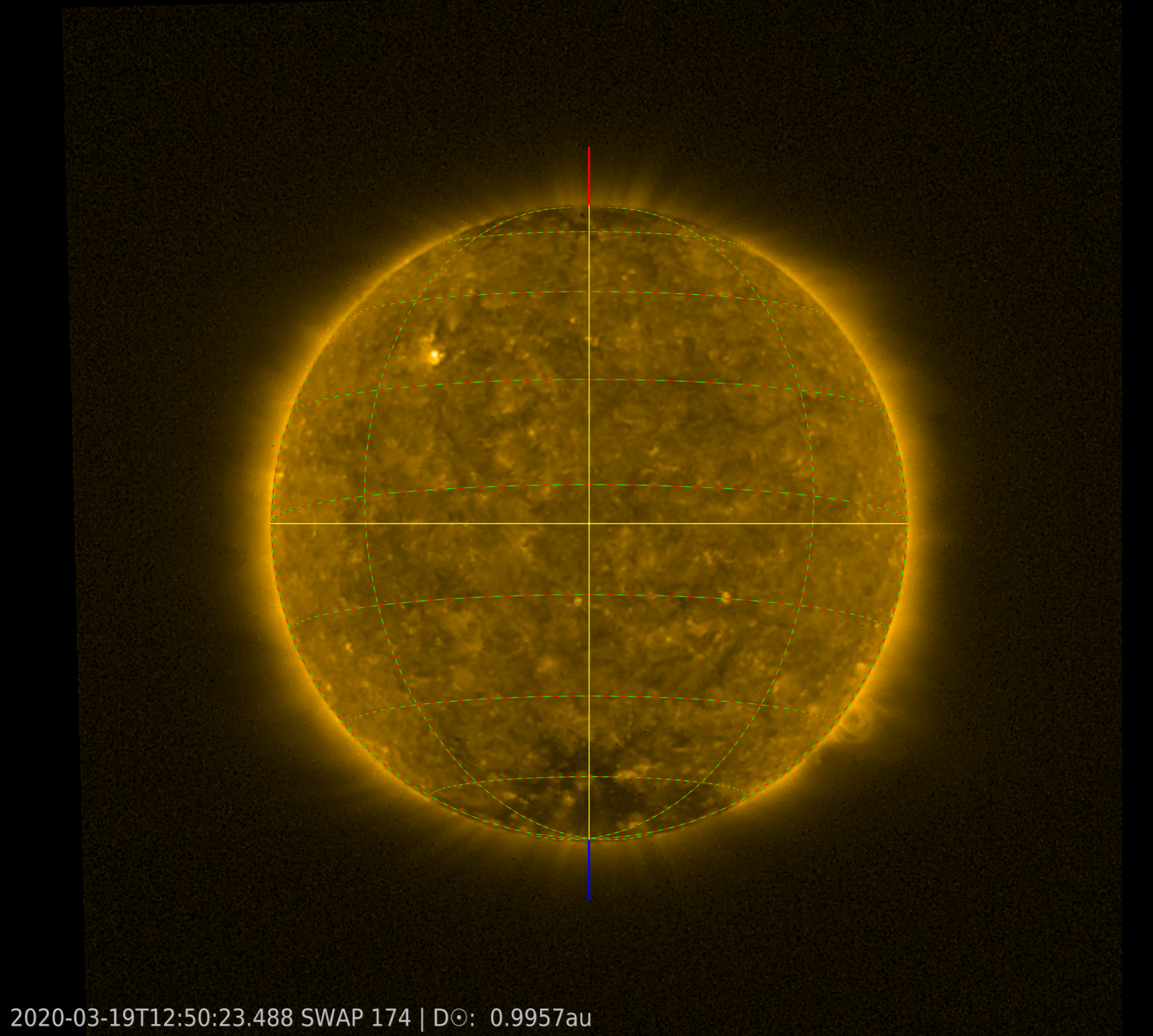

"But the shorter the wavelength, the greater the variation," says David Berghmans. "This is especially the case in the extreme ultraviolet radiation that allows us to see the corona – the ultra-hot outer atmosphere of the Sun in which many crucial processes originate. The corona is highly changeable. It looked completely different in 2020 during the previous solar minimum. The SWAP instrument on board the Proba-2 space mission (which is located in the ecliptic) showed the sun during the last minimum, with little activity visible in the corona. During the maximum we are in now, we see two parallel bands of intense activity above and below the equator, which were virtually absent five years ago."

"But what we did see during the previous solar minimum were large coronal holes near the poles", David continues. "Coronal holes are, in fact, zones with lower plasma density. But those have now disappeared. We expect coronal holes to form again, which will be detectable in EUV light. This will probably be accompanied by small eruptions that locally change the magnetic field. Such magnetic 'reconnections' have funny names such as picojets, campfires or bright points. But we do not yet fully understand their role in reversing the magnetic field on a large scale. The new observations will contribute to a better understanding of the solar cycle."

Solar dynamo: the engine of the sun

Both the solar cycle and the magnetic field are manifestations of the "solar dynamo", the engine of the sun. By studying the poles, Solar Orbiter helps answer fundamental questions about these phenomena. "The solar cycle is the phenomenon whereby the magnetic field changes polarity every 11 years. These reversals are accompanied by increased activity, such as the phase we are currently in," Anik continues. "The number of sunspots is not constant and changes through time."

"During a maximum, there are more sunspots. But the solar cycle does not run like clockwork and can last longer or shorter. The strength of each cycle, which is derived from the number of sunspots during the maxima, is also subject to fluctuations. The international sunspot number is monitored and coordinated in Belgium, and more specifically by SILSO (Sunspot Index and Long-term Solar Observations). This is one of the reasons why our country plays an important role in the Solar Orbiter research."

"Why the irregularities in the solar cycle are there is still unanswered. There are models that explain and predict the solar dynamo and the magnetic field, created by world renowned scientists. But none of these models offers a completely fitting solution because some boundary conditions are missing. There are still blind spots. But these gaps in our knowledge will be filled by the stream of new information delivered by Solar Orbiter. The poles will give us a better understanding of the sun."

The field of solar physics has clearly entered a particularly exciting new era.

Kathelijne: I am intrigued by how earth, life, and societies interact on geological and human timescales.

An immense effort is poured into GondwanaTalks.

Are my articles somehow meaningful to you? Support my work so I can keep GondwanaTalks afloat. Your contribution makes an ultra-Plinian difference. Make a one-off or recurring donation and become a:

Stromboli Strategist

(€2/month)

Tambora Trailblazer

(€4/month)

Vesuvian Visionary

(€7/month)

Already donating? Thank you so much! Other ways than paypall to donate, contact me.

-----

Recent posts:

Do you like this post? Subscribe to the short newsletter: it is sent every couple of weeks when there is a new article, and is free of heavy files and irritating gifs.

Source

Original printed article: Gespot: Bonne Kathelijne, Polen van de zon. Ruimtemissie Solar Orbiter werpt blik op last frontier van onze ster. EOS Wetenschap 11/25, p. 64-67.